Supply and Demand in the EU ETS: Powering Through the Cap

The reform of the EU’s carbon market and the free allocation regulation is now voted on. The deal was wrapped in December 2022 and was barely different from what the Commission had proposed nearly two years ago and which we had analysed in September 2021.

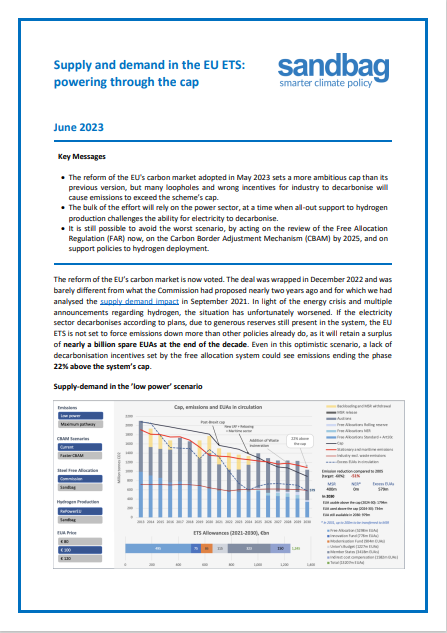

If the electricity sector decarbonises according to plans, due to generous reserves still present in the system over the decade, the EU ETS is not set to force emissions down more than other policies already do, as it will retain a surplus of over a billion spare EUAs at the end of the decade. But even in this optimistic scenario, a lack of decarbonisation incentives set by the free allocation regulation could see emissions ending the phase 22% above the system’s cap.

Free-for-all Allocation Regulation?

One uncertainty concerns the incentives set by the FAR. For many years we pointed out the absence of incentives set by the current regime. This issue was raised during the EU ETS trilogue and some wording was added to the amended Directive to remedy it. However, the Commission’s proposals so far have been quite timid and are unlikely to incentivise significant emission reductions from industry. In particular, the proposed revision fails to incentivise the use of scrap in steelmaking, which is the single largest abatement measure we have identified, with 160m tonnes of CO2 reduction potential.

Electricity: the biggest challenge

Given the lack of incentive created by free allocation rules, industry might not significantly change its emission levels for another decade. Therefore, decarbonisation efforts are likely to rely, once again, on the power sector which has already reduced its emissions (contrary to industry). We have assumed in our Simulator that electricity emissions will follow the MIX scenario set by the Commission in 2021, down to 65% below their 2015 level by 2030, as per its calculation of the impact of the Renewable Energy Directive, which amounted to (already ambitious) 7.93% annual emission reductions over 2021-30, but this scenario is less than certain to be met, mostly due to three concerns:

- The energy crisis has caused some switching from gas to coal-based generation. Meeting the 2030 carbon intensity target from 2022’s value would now require an annual 9.2% reduction on average for the coming 8 years.

- Renewable energy capacity is not currently increasing in line with what that scenario would require.

- As per the REPowerEU plan and numerous support programmes, a large part of renewables capacity is likely to be consumed by hydrogen production.

This last point could have important consequences. In the scenario, we assume hydrogen production does not increase emissions from electricity. But with large amounts of surplus EUAs still present in the system, electricity emissions be a lot higher.

The overall balance will therefore depend a lot on the amount of hydrogen produced from electrolysis over the period. In Sandbag’s recommended scenario, only 5m tonnes of green hydrogen are produced in the EU in 2030 to decarbonise steelmaking (1.5m) and existing uses of hydrogen (3.5m). There is a chance for the electricity used for this hydrogen to be truly additional1, therefore not impacting emissions from power plants.

In the REPowerEU case, promoted by the European Commission, 10 million tonnes of hydrogen are produced with little or no concern on additionality, which may lead power emissions to shoot up.

This is because a lot of power capacity used to make green hydrogen will either be taken from the existing grid (causing more fossil-based generation to fill the gap) or from renewable capacity that would have otherwise contributed to decarbonising the grid, making this already challenging 9.2% reduction in power emissions even less likely.

Such a scenario could drive emissions close to our scenario, which represents the “horror story” where emissions would follow the maximum trajectory still made possible by the ETS. This situation of high-emission electricity would see rocketing carbon prices triggering little or no reaction to reduce emissions, due to badly set incentives, and emissions finishing the decade up to 33% above the cap. It would then take enormous political will to continue the scheme on its current trajectory into the 2030s without raising the cap. Unfortunately, the Fit-for-55 deal and its aftermath (FAR, Innovation Fund reform, Hydrogen Bank, Net Zero Industry Act, etc.) make this scenario increasingly likely.

However, all is not lost. The FAR reform could, if done right, still unleash large-scale industrial decarbonisation. The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) has a review clause in 2025 which might lead to a change in scope or implementation schedule. The European Commission’s REPowerEU plan has set broad hydrogen production (and import) targets but it can still be changed.

Photo by Pixabay – Pexels

Read More:

Getting Electrification Right: The broader challenge of induced emissions

Sandbag’s latest report explores how the climate impact of electricity use depends not just on how it’s generated, but also when and where it’s consumed. Using hydrogen as a case study, the report shows how poorly timed renewable electricity use can unintentionally drive-up fossil fuel emissions — and outlines smarter paths to decarbonisation.

Feedback on the EU Commission’s draft methodology for low-carbon hydrogen

For ‘low carbon’ hydrogen to truly make a positive contribution to Europe’s transition to climate neutrality, the safeguards put in place must be meaningful. Unfortunately, this does not appear to be the case in this draft delegated act.