EU Criteria for Green Hydrogen: How They Could Increase Relience on Thermal Power and Hijack the Energy Transition

On February 13th, the European Commission released two pieces of legislation to provide criteria defining renewable hydrogen products. The so-called Delegated Acts matter because they set out how to comply with other regulations under review which will force ships, aircraft and heavy industry to use a minimum content requirement of the fuel, such as the Renewable Energy Directive, REFuelEU Aviation and FuelEU Maritime.

We are concerned that the proposed texts will:

- Incentivise reliance on fossil fuels

- Divert renewable energy otherwise useful for broader climate action

- Result in renewable electricity going to waste

- Increase the volatility of power prices

Renewable hydrogen, or RFNBO as called by the legislation, includes hydrogen fuel and its derivatives, such as ammonia, methanol and e-kerosene, produced through the electrolysis of water. Production of hydrogen derivatives that is not compliant with RFNBO standard will still be authorised and even benefit generous subsidies from various government and EU programmes, not least free emission permits under the bloc’s carbon market, but RFNBO-compliant products should get valued at a market premium thanks to the help they will provide to fuel suppliers in meeting minimum content requirements.

Although electrolytic technologies themselves do not directly emit any CO2 during production or combustion, they consume significant amounts of electricity, making them only as ‘green’ as their impact on electricity generation. According to the proposed Commission texts, the renewable nature of hydrogen produced should be assessed based on the principle of additionality, which requires that the electricity used to run electrolysers must be additional, meaning it would not have been generated had the hydrogen plants not been built. But this rule has two gaping loopholes:

- It is impossible to know whether wind farms or solar plants would have been built in an imaginary scenario.

- The additionality principle has also been watered down by numerous flexibilities and derogations, as detailed below.

Additional to what?

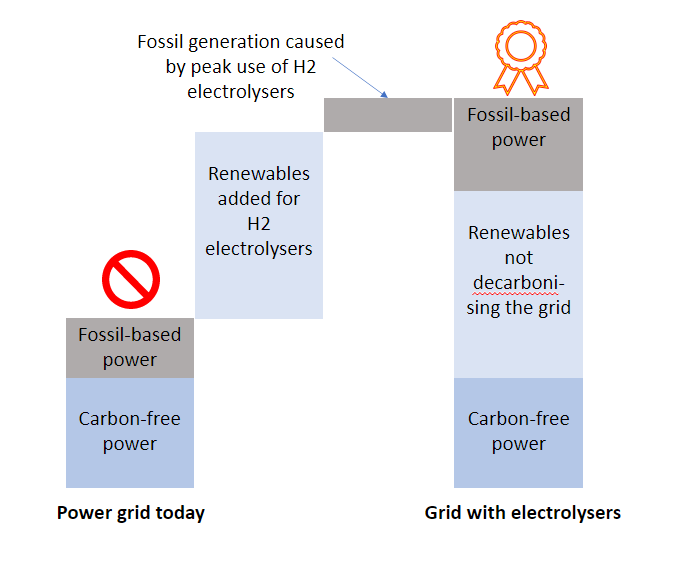

Proving that hydrogen production has a truly positive effect on reducing emissions is not easy. For example, it is not enough to prove that the electricity used to power an electrolyser comes from renewable sources, because that electricity might be taken off other useful applications, which will then have to compensate using fossil-based power. This is why the concept of additionality was introduced in the first place.

The most emblematic case of additional renewable electricity is that of a wind farm or solar plant that is only connected to an electrolyser via a direct connection, independent from the national grid. Predictably, the proposed legislation qualifies this case as eligible for RFNBO status.[1] However, whether such a renewable energy source (RES) is truly additional is debatable, as it might prevent investments in new electrical capacity needed to decarbonise the power grid regardless of hydrogen generation. For example, the land resources or building permits granted to a solar plant directly linked to an electrolyser will not benefit RES needed to decarbonise the power grid.

Arguably, at times when power prices are high and the grid is therefore having to pump electricity from coal or gas power stations, a RES that is only serving an electrolyser is not doing its job of decarbonising the industry.

A better indicator of RES additionality should have taken into account the power capacity needed to decarbonise the grid as per the EU’s grid carbon neutrality trajectory and only counted as RFNBO-compatible the capacity added to that amount. At the very least, RES should be considered additional only in countries that meet their renewable energy targets.

Better still, only the electricity used at times of low demand should be eligible for RFNBO status. The proposed legislation allows that electricity consumed from the grid at times of very low prices or excess electricity in the network (‘negative dispatch’) also qualifies for RFNBO status.[2] This principle is indeed a good use of otherwise wasted resources which truly contributes to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Additionality is not causality

Not only is the fact that hydrogen plants might use RES which may otherwise be useful to meet decarbonisation targets of the power sector not taken into account, but the causality between the investment in RES plants and RFNBO plants does not need to be proved to meet the additionality rule. A RES is considered additional simply if it started operations up to 36 months before the RFNBO production[3] (the investment in which may have been decided many years before). Before 2028, additionality will even be considered as satisfied regardless of the date the RES entered into operation.[4]

These rules make a causal connection between the two investments very unlikely, however, such a link should be a key principle, in line with the fact of considering RES that exist because of electrolysers.

Blurry temporal correlations

Not only is the additionality principle questionable in itself, but its application has also been watered down in the proposed text by a lot of flexibility mechanisms. These were brought in based on the principle that it is technically easier to connect RES to electrolysers via the grid than directly together, but they make the relation between what is generated by the RES and what is consumed by the hydrogen plant much less obvious.

Until 2030, if an electrolyser is connected to a RES via the grid (and a power purchase agreement exists between the two)[5], the electricity it consumes is considered as coming from that RES as long as it is generated in the same month.[6] It will only be in the next decade that the temporal correlation between electricity generation and hydrogen production increases in frequency, shifting to an hourly basis.

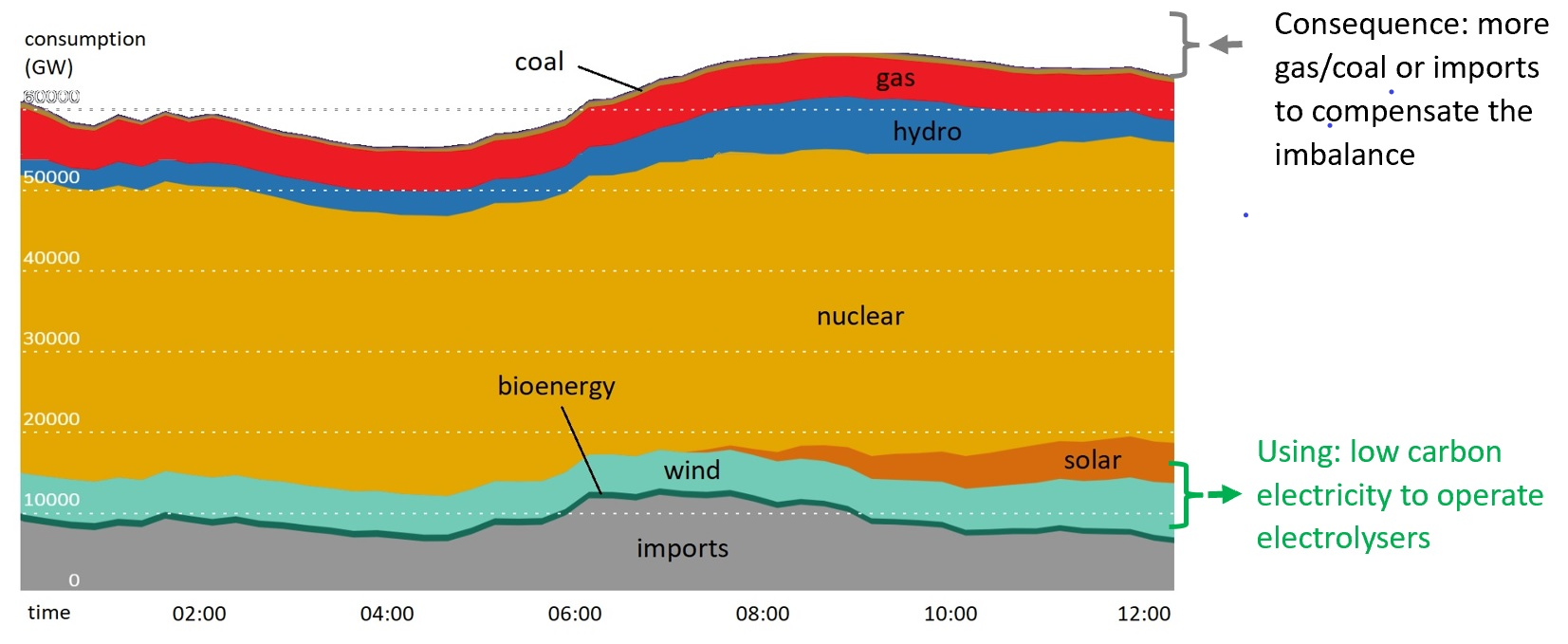

This monthly correlation principle could lead to dangerous imbalances in the power grid. If electrolysers operate at times when associated renewable sources are insufficient, they may draw power from the grid and create an imbalance that would trigger thermal power plants to stabilise the network. During such instances, electrolysis would temporarily increase the carbon intensity of the power grid, while a share of produced hydrogen at the end of the month would inaccurately be labelled as ‘renewable’.

By comparison, the criteria for consumption of low-demand power as described in article 6 paragraph 3 (see appendix) require that the electricity is consumed in the same hour as the power price is recorded as low enough. It is therefore surprising that other additionality principles allow for timing differences between production and consumption of up to a month.

Comparing apples and oranges

Flexibilities introduced by the Commission’s text even go one step further, exempting hydrogen producers altogether from matching the timing of any power consumption with renewables generation[7] if their electrolysers are located in countries with a high share of renewable electricity or a low carbon intensity.[8]

This exemption is puzzling, as the share of RES or the carbon intensity of the local power grid before new electrolysers come online are no indication whatsoever of the impact electrolysers will have on the grid throughout their operational life. This is because the new demand they create will have to be met by new generation. If that extra capacity is thermal (local or imported), then the true effect of the electrolysers is an increase in purely thermal power use. This is what would happen in the example illustrated below, taken from the French grid: despite a low carbon intensity, any amount of low-carbon power drawn from the grid would have to be compensated for by an increase in thermal domestic or imported production to meet the demand.

Double counting

Using the grid’s average RES share or grid intensity to qualify for RFNBO is also misleading if part of the RES connected to the grid includes the RES used to produce the said RFNBOs.

The proposed text stipulates that the carbon intensity of electricity “shall be determined at the level of countries or at the level of bidding zones [the geographical areas within which market participants can buy and sell electricity[9]]”,[10] making no distinction between the electricity generated for hydrogen and for other uses, between power produced and power consumed (imports are simply ignored) or even between power plants connected to the grid or not.

As a result, in a country with a non-eligible grid (low share of renewables or high carbon intensity), the addition of renewables to run electrolysers will count positively towards the country’s compliance to the criteria, even if that means a total increase in emissions due to unintended consequences such as the ones outlined above.

A more relevant metric to measure the impact of electrolysers on the grid would involve deducting from total generation any renewable electricity dedicated to powering electrolysers.

Turning a blind eye

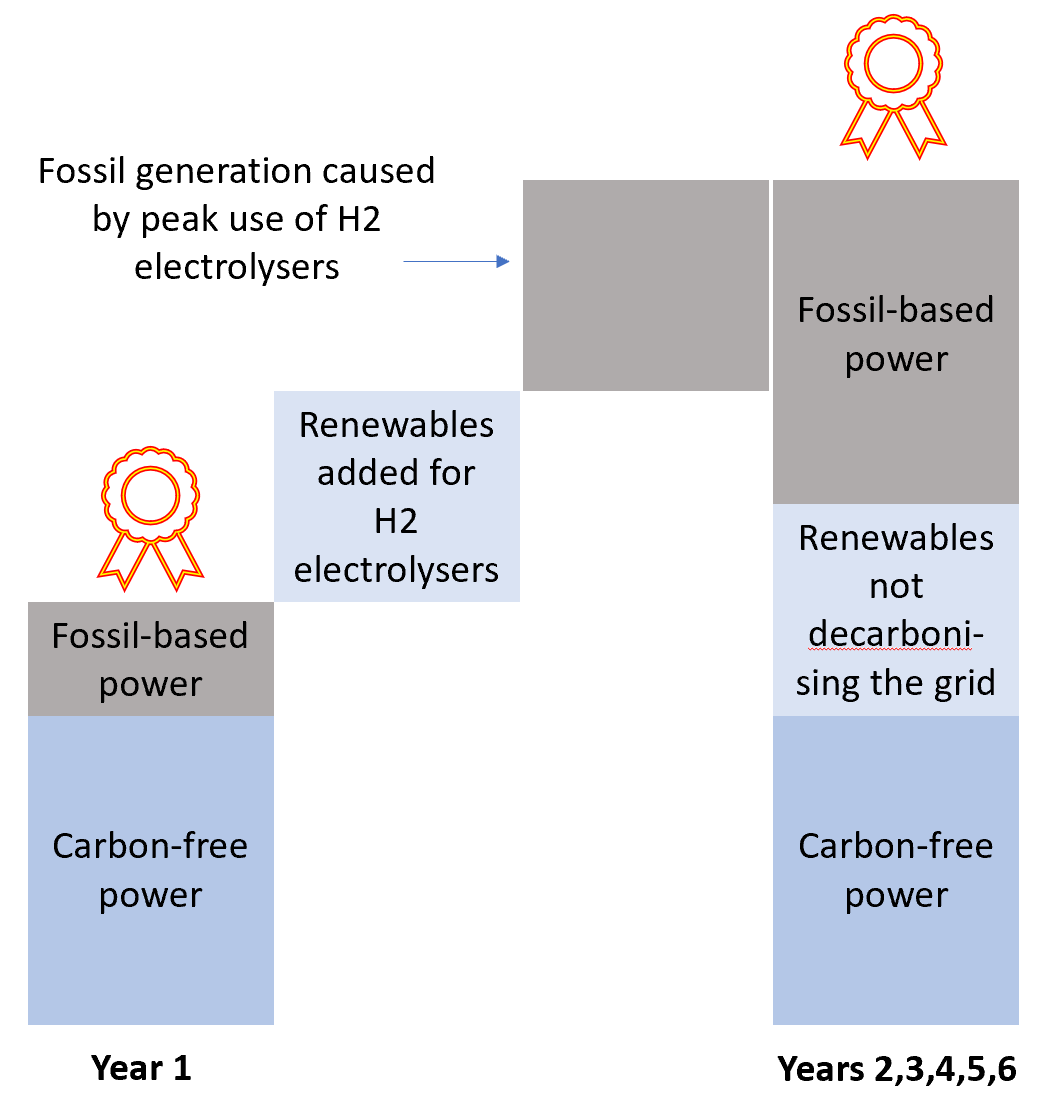

The proposed text states that if a grid meets the low-carbon or high-RES grid criteria one year, it will automatically be considered compliant for the next five years. In other words, the regulator turns a blind eye on any deterioration caused to the grid by RFNBOs for five years. This leniency is odd, to say the least, especially given the scale of deployment objectives set to RFNBOs for this decade, which will cause large changes to national grids.

The price to pay

The scale of the demand for hydrogen derivatives meeting RFNBO status is still very uncertain, as other regulations setting RFNBO content requirements are still being drafted.

Hydrogen from water electrolysis, whether or not compliant with RFNBO status, is set to benefit from a lot of support, at great expense for the European taxpayer, such as free emission allowances and compensation for indirect carbon costs under the EU’s carbon market, but also the Innovation Fund and national support schemes. In addition, imports of hydrogen derivatives are likely to face low requirements as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) exempts any emissions from electricity used for their production.

Setting higher requirements for RFNBOs could have created a higher-value market for hydrogen derivatives that better serve the common good by using up excess grid electricity (thereby stabilising electricity prices and reducing grid imbalances) and accelerating the development of renewable energy.

Instead of this, the proposed regulations merely validate the use of any renewable electricity for hydrogen, including if it drives up the production of power from fossil sources such as natural gas and increases volatility. By creating incentives at so many levels, it risks diverting precious renewable electricity to wasteful and unsustainable uses, making renewable electricity more scarce than it already is.

Recommendations

– Consider renewable energy sources (RES) as additional only in countries that meet their renewable energy targets.

– Stop double-counting: deduct from the calculations of i) proportion of renewable electricity and ii) grid emission intensity, any renewable electricity used to produce hydrogen. Make the same deduction when testing a country’s achievement of its renewable energy target.

– Stop comparing apples and oranges: there is no reason to exempt a country from temporal correlation simply because it has a low-carbon grid.

– For a hydrogen production facility connected to a RES via the grid, replace the condition of a maximum 3-year interval between the RES’ operation start and hydrogen production with a credible test of causality between the two investments.

– Repeal the transition period removing additionality requirements altogether until 2028.

– Mandate hourly correlation instead of monthly correlation

Notes

[1] Article 3 of Delegated Regulation on RFNBO production rules

[2] Articles 4.3 (network imbalance requiring downward redispatching) and 6 paragraph 3 (power prices below €20/MWh or 0.36 times the price of an emission allowance, ensuring no fossil fuels in the electricity mix).

[3] Article 3(b) of Delegated Regulation on RFNBO production rules. Also Article 5(a) for the case of assets connected together via the grid.

[4] Article 11 of Delegated Regulation on RFNBO production rules.

[5] Article 5 of Delegated Regulation on RFNBO production rules

[6] Article 6 paragraph 1 of Delegated Regulation on RFNBO production rules

[7] Although, for low-carbon grids, a power purchase agreement must exist with some RES – Article 4(2)(a) of Delegated Regulation on RFNBO production rules

[8] Renewable generation ≥ 90% or a carbon intensity <18gCO2eq/MJ on average over the previous calendar year, as per Art 4.1 and 4.2 of the Delegated Regulation on RFNBO production rules

[9] According to the EU Electricity Market Design Regulation

[10] Part C of Annex to Delegated Regulation on RFNBO emission assessment: “Methodology for determining greenhouse gas emissions savings from RFNBO”

Photo by Matthew Henry on Unsplash

Read More:

The CBAM dividend for Namibia and Ghana

This research note shows that Namibia and Ghana are likely to benefit from the CBAM, as EU price increases linked to the EU ETS outweigh CBAM fees under current exports. It also sets out transparent transformation scenarios, based on announced industrial projects, to show how expanded and lower-emissions production could further increase export revenues over time.

Steel labelling: Beyond the sliding scale

As EU policymakers debate how to certify low-carbon steel, Sandbag’s new briefing analyses the “sliding scale” method — and outlines why it may hinder rather than help decarbonisation. A new model is proposed based on product-specific benchmarks, multi-tier ratings, and circularity incentives.

Chemicals in the CBAM: Time to step up

Sandbag’s latest brief explains why the EU CBAM must be expanded to cover key chemical value chains. With chemicals and refinery products responsible for 30% of industry emissions, phased inclusion is critical to prevent carbon leakage and phase out free allowances.