Fixing the Innovation Fixation

The EU’s Innovation Fund, launched in 2018, is the EU’s programme for funding cutting-edge low-carbon technologies. To be eligible, projects must be, according to the European Commission, highly innovative, cost-efficient, mature, scalable, and have a significant emission reduction potential. The Innovation Fund is financed using revenues from the Emissions Trading System (ETS), under which certain sectors have to buy emission permits (allowances) in order to be allowed to pollute.

The Innovation Fund is currently being overhauled to reflect recent changes to the ETS.

Below is Sandbag’s feedback submitted to the European Commission’s Innovation Fund Expert Group, which coordinates stakeholder participation for the revision.

Sandbag welcomes the opportunity to present input into the Innovation Fund’s Expert Group in response to the Commission’s concept note presented on 29 March 2023. This input follows and reflects the concerns expressed in Sandbag’s report Spend Smarter: a bit of advice on innovation financing published in December 2022.

Grants vs. contracts

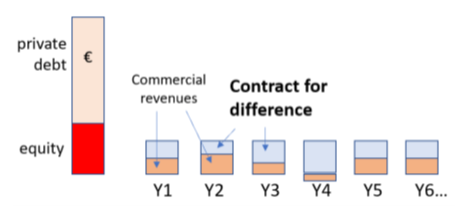

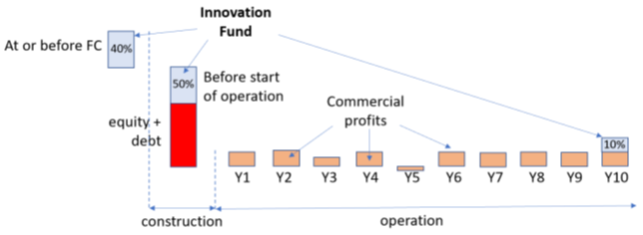

We welcome the introduction of contracts (fixed premium or contract for difference) rewarding projects on the basis of their performance. Currently, up to 90% of Innovation Fund payments are made before a project even starts operating, which is only appropriate for projects facing high technology risk.

Payment schedule of a contract for difference

Upfront funding should be avoided as much as possible and only be used in duly justified situations, because it has a number of drawbacks:

– it crowds out private investment;

– it doesn’t incentivise performance;

– it creates more risk of projects closing down (if their profits become negative);

– it makes the grantor (EU taxpayers) bear all the risks other than technological as well. This includes bad management, construction errors, offtake issues, supply issues, counterparty risk, failing operator, commercial strategy, legal, HR etc.

The Innovation Fund’s eligibility criteria are based on projects’ degree of innovation, which does not always reflect the value at technological risk of projects. For example, a windfarm project was selected for using secondary steel, which is considered innovative (having not been done before) and probably expensive, but not risky from a technological standpoint for the windfarm itself. Another example is a technology that is not commercially available in a specific Member State even though it is elsewhere.

According to IF rules, the project would qualify as “innovative” for the Member State despite the technology being mature and any risk of deploying it being related to other aspects than technology (for example, commercial or logistical). In those cases, subsidies could be paid on the basis of performance instead of upfront because the EU should not bear these other risks.

The criteria for awarding grants rather than contracts have not been clarified by the Commission. We urge that the amount of any grants should be exclusively based on the value at technological risk (value at risk is a measure of the loss incurred in a conservative scenario).

Circularity objectives and resource savings

The amended ETS directive commands that projects supported by the Innovation Fund “contribute to energy and resource savings”, “with a view to their broad roll-out across the EU” (Art.10a(8)), yet the degree of resource saving is only covered by the IF criteria in optional ways:

– As part of the “degree of innovation” criteria, the fact that a project also saves resources can be considered a “plus”, and

– In the “scalability” criteria, resource-saving qualities may contribute positively to the score.

Resource-saving should not be optional but a requirement for IF support, as it is key to the scalability of projects. In the current “scalability” criteria, scalability is rated at local, sector and economy-wide level in equal proportions (with 3 marks out of five leading to 1 mark out of 15), which dilutes the flagging of unsustainable practices, as projects that are unsustainable at economy scale (e.g. power-to-hydrogen-to-power without storage; hydrogen for domestic heating…) might be considered scalable for the local economy or even the sector, and therefore still be given a decent score. This concern is all the more important given that a key assumption underlying the methodology for GHG avoidance estimates is that grid electricity is carbon-free, i.e. there is an unlimited supply of 24-hour zero-carbon electricity.

Instead of having circularity covered by optional sub-criteria, we recommend, alongside Carbon Market Watch, that resource saving be explicitly assessed in a mandatory criterion with equal importance as degree of innovation and that the use of scarce resources be considered at economy scale rather than at local or sector scale.

Relevant costs

We welcome the proposed clarified definition of relevant costs and the fact of using the same definition of relevant costs for small- and large-scale projects, which takes into account both costs and benefits.

Cost efficiency; cumulation rules

The “cost efficiency” criterion rates a project’s IF funding per tonne of CO2 avoided. This may be relevant to CINEA in its management, but what matters is the total cost of projects to public finances and the wider economy, which this measure fails to capture, to ensure an efficient allocation of funds. In a context of multiple subsidy schemes (with e.g. Horizon 2020, State aid to IPCEI projects, the Net Zero Industry Act etc.), an expensive project might get a high “cost efficiency” rating by IF standards simply because of receiving a lot of funding from outside the Innovation Fund, thereby requiring only a small top-up from the IF. But this measure is relevant for neither EU taxpayers nor the economy.

Instead, the “cost efficiency” criteria should take into account all funding needed by the project, including not only IF and State aid but also the allocation of free emission permits under the EU ETS, indirect support received through public-funded infrastructure or the use of subsidised inputs. It should include private funding as well, to encourage truly efficient capital allocation, with a view of lowering competitive distortions between projects and technologies.

This principle should also prevail in the “cumulation rules” applied to competitive bidding.

GHG avoidance estimates

The estimate of GHG avoidance is the most important criterion for eligibility as well as for the ranking of projects. Yet we are concerned about some governance issues in its calculation.

Only one expert

Despite there being five experts on each expert panel, and the consensus nature of project rating between those experts, only one expert is asked to review estimates of GHG emissions avoidance and that expert’s work is not visible to the other four. This is a major concern, especially as calculation guidelines are complex and one sole expert might fail to flag errors. Instead, the whole panel of experts should review estimates of GHG emissions avoidance. As the skills required to apply the methodology (mostly mathematics) are shared by all experts, this should not even require any change in recruitment.

Errors vs. optimistism

According to IF rules, GHG estimates can only be challenged by experts if they contain errors, either “clerical” or “manifest”. Clerical errors can simply be corrected, whereas manifest errors make projects fail altogether so they are only flagged in blatant cases.

Many projects however contain a third type of estimation discrepancies that are neither clerical nor manifest errors, but are simply caused by the use of unrealistic assumptions. Many factors may influence a project’s GHG avoidance estimate: technological performance, operational performance, ramp-up speed, availability and cost of inputs, profitability etc., many of which are reviewed by the experts but only as part of their rating of technical and financial maturity. For example, the likelihood of a project achieving the claimed avoidance is one of many sub-criteria of technical maturity. Yet, only the value of GHG emissions avoidance claimed by applicants is considered in the rating of criteria that count towards the final score:

– Absolute emissions avoidance

– Relative emission avoidance compared to ETS benchmarks

– Cost efficiency

This tends to favour over-estimation. Instead, a likely value should be estimated by experts for use in the rating of the other criteria using this information.

Comparison with outdated benchmarks

We are also concerned that the criteria on GHG emission intensity is based on the EU ETS benchmarks. Those benchmarks reflect emission intensity levels for the 10% lowest-emitting plants observed back in 2016-7 and corrected by a maximum 2.5%, so for some sectors they are higher than best available technologies already installed in the EU.

Together with Carbon Market Watch, we recommend updating the reference for GHG abatement estimation in line with climate neutrality objectives.

PDA attribution

We are concerned about the Commission’s proposal to make Project Development Assistance (PDA) available to all projects meeting the GHG avoidance and degree of innovation criteria. By doing so, the EU could spend public money even on projects that are not sustainable at the scale of the EU. We recommend that resource saving be a key criterion in the attribution of PDA.

Sandbag’s recommendations

- Avoid upfront funding except for projects with a high technology risk.

- Grants made under the IF should exclusively consider the value at technological risk, rather than the degree of innovation.

- Resource-saving is key for a project’s scalability. It should therefore be explicitly assessed as part of a mandatory criterion with equal importance as a project’s degree of innovation. It should also be made a key criterion for the attribution of Project Development Assistance (PDA).

- To prevent burden on taxpayers and the economy, the “cost efficiency” criteria should consider all project funding, such as IF and state aid, free emission permits under the EU ETS, publicly funded infrastructure support, subsidised inputs, and private investment.

- For a project’s greenhouse gas (GHG) avoidance estimates to be as accurate as possible, they should be

- Reviewed by the whole panel of experts, not just one.

- Independently estimated by the expert panel for use in the rating of the other criteria using this information.

- Assessed with reference to updated benchmarks to ensure a project’s innovativeness and contribution to emissions avoidance.

Photo by Anil Xavier on Unsplash

Read More:

Scrap Steel at Sea: How ship recycling can help decarbonise European steel production

As Europe seeks to decarbonise its steel industry, a new Sandbag report highlights an overlooked solution: high-quality scrap steel from retired ships. With up to 15 million tonnes of certified scrap available annually, ship recycling could meet 20% of EU steel scrap demand — if policy gaps are addressed.

ICC reform and expansion risks diverting ETS revenues from real climate action

Sandbag and 14 other organisations urge the European Commission to reform, not expand, the ETS Indirect Cost Compensation scheme — warning that current proposals risk diverting climate funding into untargeted fossil subsidies.

Sandbag’s feedback to the call for evidence on the Circular Economy Act

Sandbag welcomes the Circular Economy Act (CEA) as an important step to accelerate the transition to a circular economy in the EU. Progress in this area has been slow and this act is sorely needed to address systemic issues holding back circularity, including the current fragmented approaches across Member States.