From Process to Product: A Fix to the Allocation of Free Emission Permits to Industry

On 18 April 2023, Sandbag presented to the European Commission’s Expert Group on Climate Change Policy a proposal for reforming the granting of free emission permits to industry under the bloc’s carbon market. Our proposal aims to incentivise the switch to lower carbon production methods, which the current way of handing out free allowances does not.

What is free allocation?

Free allocation is a measure whereby sectors are supported for having to pay to pollute under the Emissions Trading System (ETS). Free Allowances are made available to industries that are susceptible to moving their business to non-EU countries in order to avoid having to pay to emit in the EU. This decision, known as carbon leakage, would not only lead to a loss of jobs and revenue in the EU, but also do nothing to combat climate change.

In some sectors, free allocation will eventually be replaced with a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). In the transition period for these sectors, and for the non-CBAM sectors, free allocation therefore serves as a protection measure for EU plants and a matter of revenue distribution, as it reserves a share of the carbon market’s trillion euro value for EU-based industrial plants instead of spending it in other ways. However, this system is heavily flawed: it creates obstacles to decarbonisation and innovation, and significantly undermines the carbon market itself.

What is the problem?

Free allocation is based on the way goods are produced rather than the goods themselves: it is process-based. This leads to differentiated allocation methodologies for the same type of goods disincentivising transition to cleaner processes, as more polluting processes receive more permits. For example, in the case of steel, the more polluting blast furnace production route typically receives about 25 times more free permits than the cleaner electric arc furnace route.

For incentives to be improved, the amended ETS Directive stipulates that “free allocation for the production of a product should take into account the circular use potential of materials and be independent of the feedstock or the type of production process, where the production processes have the same purpose” (Recital 8). Although this is a great concept in theory, implementing it requires a few changes, as we show here for the case of steel.

A solution for steel: product-based benchmarks

In Europe, steel is produced using processes with very different carbon intensities. This is why, although steelmaking using electric arc furnaces (EAF) represented 43.6% of all EU steel production in 2021,1 the plants involved in this operation only received 3% of the total free allowances for steel while the other 97% went to plants using the more polluting blast furnace / basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) route.

The main reason for these different treatments is that EAF steelmaking can use a lot more scrap than BF-BOF steelmaking, which reduces its carbon footprint dramatically. By securing more free emission permits for BF-BOF processes than for EAF processes under the EU ETS, the current allocation benchmarks are an obstacle in the way of a large-scale switch to electric steelmaking.

It would be tempting to think that allocating, without distinction, the same number of free permits to the EAF route as the BF-BOF route is currently receiving would solve the problem. However, this would in fact lead to a near doubling of (preliminary) free allocation. But there is another solution.

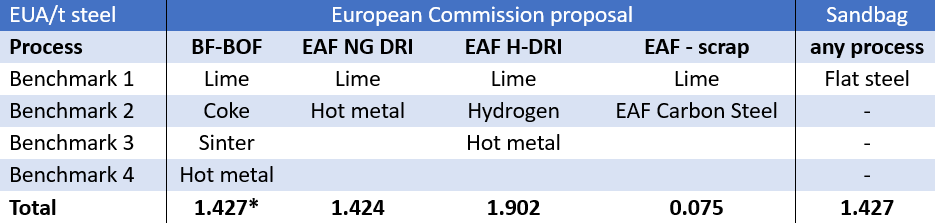

EU steel production currently differs depending on the type of end product: flat or long. Under the current regulation, free allowances are given to plants involved in each stage of the process such as lime making, coking, ore sintering, direct reduction etc., regardless of the end product. Each process has its own allocation ‘benchmark’ setting the number of free permits given per tonne of each intermediary product. Instead, free allocation could happen slightly further down the value chain, where hot steel becomes an actual product, long or flat steel. Different benchmarks should then be linked to flat products and long products. This would incentivise the electrification of flat steel production without significantly changing the number of emission allowances allocated.

The above method also applies to steelmaking using hydrogen to decarbonise production. In the method proposed by the European Commission, free allowances in hydrogen steelmaking would add up using the ‘hydrogen’ and the ‘hot metal’ benchmarks, which would lead to different amounts of free allowances compared to other processes. Covering hydrogen steel under the ‘flat steel’ benchmark would eliminate differences between processes.

In a concept note circulated to the Expert Group on Climate Change Policy, the European Commission proposed to slightly modify the way free allowances are given to industries. However, it fails to create the conditions set out in Recital 8 of the Directive, that free allocation should be independent of the feedstock or the type of production process.

Free Allocation per tonne of flat steel using different processes and feedstocks

The figures above show how different EUAs are allocated per process and how this incentivizes BF-BOF more than EAF processes when hydrogen is not used as an input. Also, with the current proposal by the European Commission, there is a very minimal incentive for the use of more scrap in steel production since the free allocation is calculated based on a tonne of intermediate material e.g. the sponge iron for EAF-DRI. This independence of free allowances from scrap discourages companies from maximising the available steel scrap within the EU.

In our last published report on steel, we estimated the cost of switching from BF-BOF to EAF with increased use of scrap at €56 per tonne of avoided CO2, and that a carbon price of €83 would create incentives to even increase scrap collection. This cost is lower than the current market price of emission allowances. By awarding free allowances for the use of scrap, our proposal would create sufficient incentives to increase the use of scrap in flat steel product manufacturing.

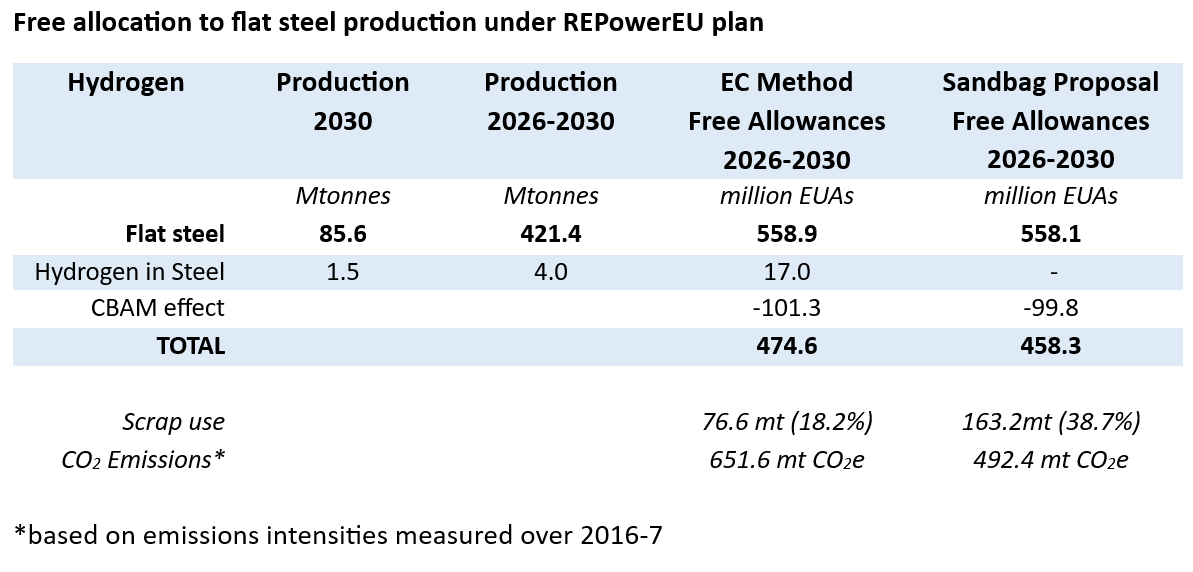

The impact could be considerable. The following table illustrates how, with a similar amount of free allocation, a large amount of emission reduction (160 million tonnes of CO2) could be achieved through this incentive, taking into account the REPowerEU plan to produce 1.5m tonnes of hydrogen for steel by 2030.

Free allocation to flat steel production under REPowerEU plan

Next steps:

The European Commission is expected to adopt the Delegated Acts defining the revised benchmarks in mid-July. The European Parliament and the European Council will then have two months to examine them. The Acts are expected to become law by the end of the year.

Sandbag in the mediaThis policy brief was also reported on by Carbon Pulse: Think-tank calls for shift in EU ETS free allocations ahead of phaseout |

Photo by Ant Rozetsky on Unsplash

Read More:

The EU CBAM gives a boost to Algeria’s iron exports

Sandbag’s brief assesses how the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) may affect Algeria’s iron and steel exports. It finds that although Algeria’s overall exposure to CBAM is limited, rising EU carbon costs are likely to increase EU market prices, with implications for the revenues and competitiveness of Algerian exports.

CBAM and Fertiliser Inflation in 2026: The facts behind the numbers

Estimates suggesting that the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) could increase fertiliser prices by up to 30% have brought a central question into focus: how

significant is the inflationary impact likely to be?

The CBAM dividend for Namibia and Ghana

This research note shows that Namibia and Ghana are likely to benefit from the CBAM, as EU price increases linked to the EU ETS outweigh CBAM fees under current exports. It also sets out transparent transformation scenarios, based on announced industrial projects, to show how expanded and lower-emissions production could further increase export revenues over time.