We took part in a targeted survey run by the European Commission’s DG TAXUD on methodologies used to calculate embedded emissions and the rules for adjusting CBAM obligations alongside free allocation under the ETS.

Our proposal: free allocation should be reformed to close the ‘DRI loophole’.

The CBAM’s DRI loophole

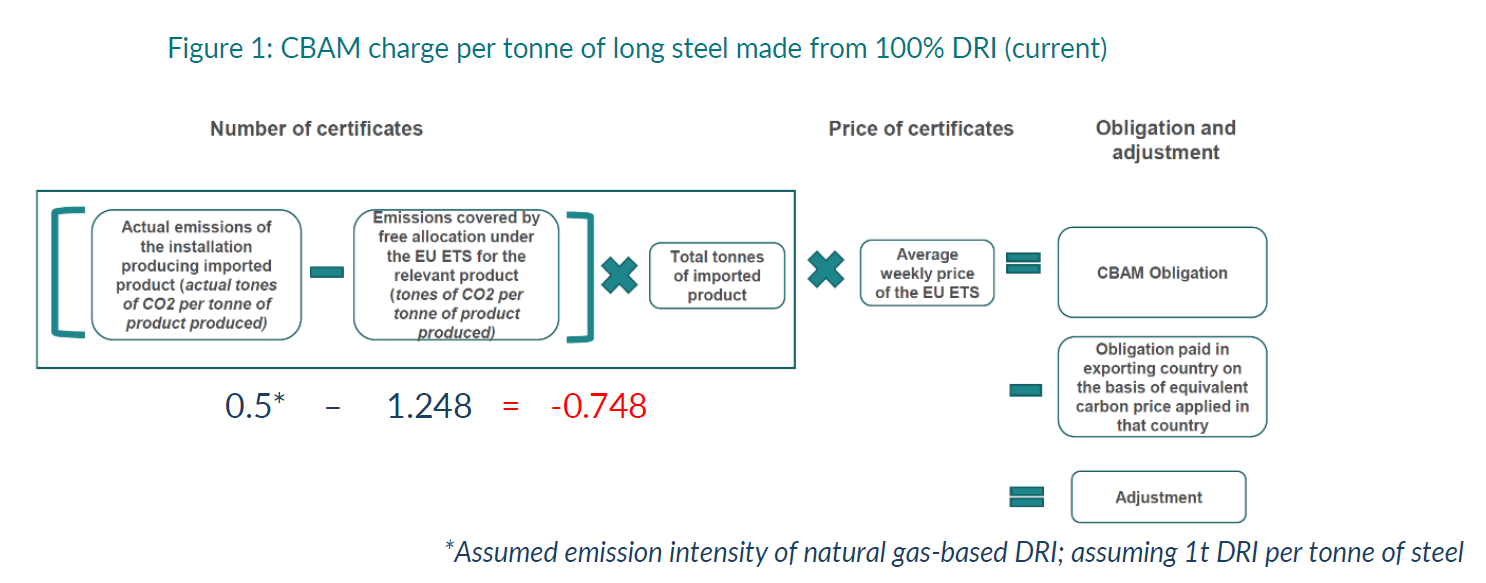

The current free allocation system under the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) is creating a loophole for long steel products under the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), charging negative CBAM to importers.

The number of free emission allowances (EUA) received by steel plants under the EU ETS depends on the process they use as defined by ‘product benchmarks’:

- As per the ‘hot metal’ benchmark, a plant producing ore-based metallics (OBM) such as hot metal or direct reduced iron (DRI) will receive 1,248 emission allowance (EUA) per tonne of hot metal / DRI produced (Sandbag’s estimate for 2026-2030).

- As per the ‘EAF carbon steel’ and the ‘EAF high alloy steel’ benchmarks, an electric arc furnace will receive only 0.145 or 0.176 EUA per tonne of steel produced, depending on the alloying content (Sandbag’s estimate for 2026-2030).

Many third countries make long steel products from DRI using natural gas, which typically emits about 0.5 tonne of CO2 per tonne of DRI produced. The CBAM is calculated by the below equation, which will therefore give a negative value for the DRI portion of imported steel product.

In contrast, European manufacturers of long steel products tend to use electric arc furnaces with up to 100% scrap, paying for their emissions but only receiving 0.145 (or 0.176) free allowance per tonne of steel produced.

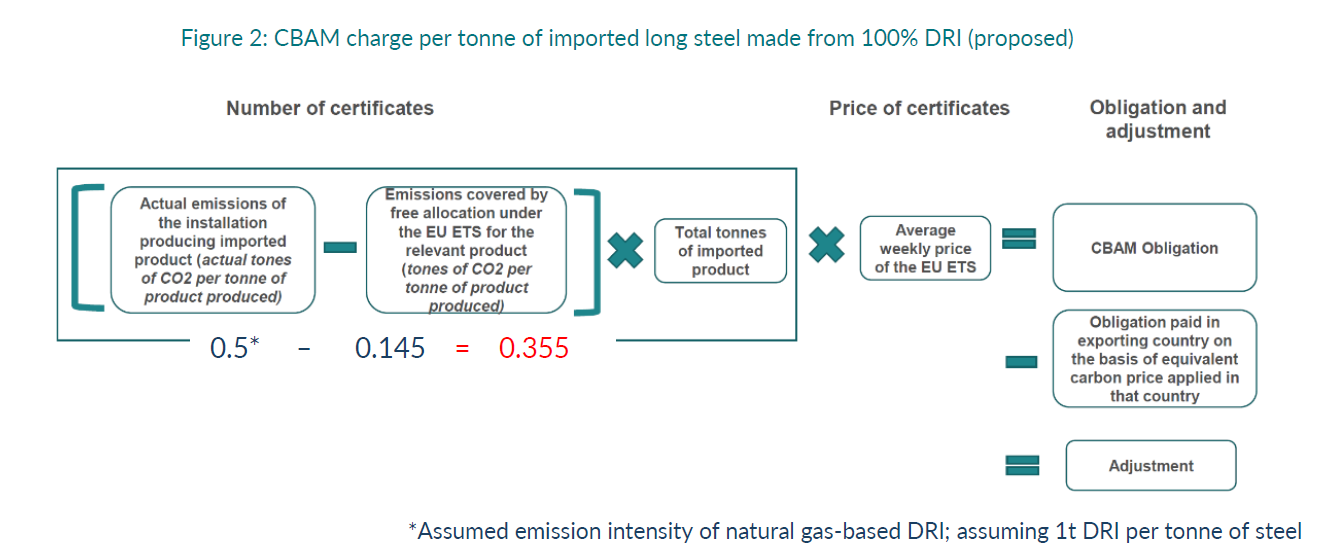

Solution: calculate free allocation based on steel output

Unlike the EAF benchmarks, the hot metal benchmark awards free allowances based on an intermediary material (DRI or hot metal) rather than steel output. This creates perverse incentives within the EU ETS, by discouraging the recycling of steel scrap to the benefit of more polluting inputs based on the transformation of iron ore with coal and gas. Instead, the hot metal benchmark should award free allowances based on either flat or long steel output, just like the EAF benchmarks do. The benchmarks should be independent of the manufacturing process, and instead award:

- 1,123 European allowances (EUA) per tonne of flat steel produced (regardless of the process used)

- 0.145 or 0.176 EUA per tonne of long steel produced (regardless of the process used), depending on the alloying content.

This would make scrap recycling more attractive to flat steel manufacturers. It would allow their transition from blast furnaces to (less polluting) electric furnaces, which can use more scrap, without losing out on free allocation.

But it would also ensure that the CBAM does not give an unfair competitive advantage to imports of long products made from DRI made from fossil fuel, as illustrated by the below figure.

The Free Allocation Regulation (FAR) was reformed in 2024. During consultations preceding that reform, Sandbag had made a proposal addressing the perverse incentives created by the amended regulation. The DRI loophole is another negative consequence of the bad choice made in that regulation.

By amending the hot metal benchmark again, the EU has a chance to “kill two birds with one stone” and correct incentives for both imports (under the CBAM) and EU-made steel products (under the EU ETS).

Photo by Samuel Wölfl from Canva

Related publications

CBAM impact on US trade: an analysis

Sandbag’s September 2025 research note explores the impact of the EU’s CBAM on US exports. It finds that even with expanded scope, the financial impact remains marginal, and US carbon pricing could turn net costs negative.

The EU CBAM: A Two-Way Street to Climate Integrity?

Supported by the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Sandbag’s report examines the impact of the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and the gradual removal of free allowances on third-country exporters. The joint implementation is expected to raise production costs for both EU and non-EU producers, leading to higher prices for CBAM-covered goods in the EU.

Strengthening the CBAM — by default

The consultation aims to address concerns that the CBAM has loopholes that could distort competition between products manufactured in the EU (covered by the EU ETS) and imported goods. Our response sets out proposals for how the design of the CBAM could be improved in these regards.