Closing the CBAM scrap loophole – A critical move for climate & competitiveness

This joint op-ed by Norsk Hydro, Alcoa, Bellona Europe and Sandbag was published by Carbon Pulse.

The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) was established to extend Europe’s carbon pricing to imported products, aiming to create a level playing field between European industries and those from regions with less ambitious climate policies. However, in its current form, the CBAM fails to assign equal carbon costs to imported aluminium products as it does to those produced in Europe.

In Europe, the carbon cost follows the metal regardless of the production route or the use of industrial scrap, ultimately passing the cost to the consumer. In contrast, the CBAM does not allocate carbon emissions to re-melted industrial scrap used during production. This loophole allows re-melted aluminium to enter the EU without incurring CBAM costs, despite significant emissions during production. It undermines the CBAM’S climate goals and the competitiveness of the European aluminium industry, particularly affecting aluminium recyclers in Europe. Fortunately, EU decision-makers still have time to address this issue and close the loophole.

The CBAM must assign emissions to process (pre-consumer) scrap to align with the EU ETS on carbon costs.

Aluminium is crucial for Europe’s greener future, supporting 1 million EU jobs and key sectors like construction and technology. It’s vital for Europe’s strategic autonomy, as highlighted in the Critical Raw Materials Act and the Net Zero Industry Act. EU aluminium production is also subject to the carbon emissions compliance obligations of the EU ETS, which aims to reduce the sector’s carbon emissions over time but also affects the competitiveness of EU industry in the global market.

The CBAM’s stated aim is to prevent carbon leakage by ensuring that imported goods bear similar carbon costs to EU-produced goods. This way, the EU is trying to ensure that European industry can decarbonise without de-industrialising. However, this principle of equal attribution of carbon costs is currently not applied for imports of aluminium products made from re-melted process scrap which is a significant part of global aluminium stocks.

In the aluminium market, costs are passed through the value chain. In the EU, this includes carbon costs: EU primary aluminium producers pay for production emissions, and these costs follow the aluminium through the value chain to the consumer. This holds true even from parts of metal that are cut off during the production process and re-melted into new products. So-called industrial, process, or pre-consumer, scrap is treated and traded similarly to primary aluminium, as they have the same properties and are interchangeable products.

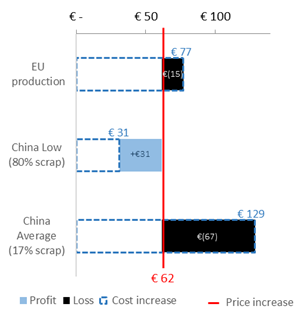

The CBAM, on the other hand, fails to assign the same emissions and costs to imported aluminium products made of pre-consumer scrap. This results in a much lower carbon cost for imported aluminium products containing remelted industrial scrap compared to similar products in Europe. The CBAM methodology overlooks the initial production emissions and associated carbon costs from the metal that becomes process scrap, which are well-accounted for and evenly distributed in the EU system. It is expected that Chinese aluminium exporters could easily turn the impact of the CBAM from a €67 cost into a €31 profit per tonne of aluminium, simply by increasing the scrap content of their metal.

Figure: Impact of the CBAM scrap loophole in euros per tonne unwrought aluminium

Source: Sandbag[1]

The CBAM should thus levy equivalent carbon costs on imported aluminium products and strengthen the carbon accounting methodologies it relies on. In its current form, the CBAM could end up undermining both the production of low carbon primary aluminium and recycling of aluminium within Europe. It is a paradox that a technicality in one of the flagship climate instruments of the Green Deal risks undermining European industries vital for the green transition and for fulfilling the climate objectives of the EU.

Regardless of why the European Commission has chosen this solution in the reporting phase, it must be changed for the permanent phase of the CBAM which begins in 2026.

Not all scrap is equal: different carbon costs for EU producers.

There is a distinction between process (pre-consumer) scrap and post-consumer scrap, even though they are counted equally by the CBAM. Pre-consumer scrap consists of cut-offs and leftovers from production. It retains the same properties and market value as primary aluminium and hasn’t completed its lifecycle: it has never been a product. Yet EU producers will face fast-increasing carbon costs for this type of scrap as free allocation is phased out in the EU ETS.

Post-consumer scrap, on the other hand, includes items like used beverage cans and car parts that have finished their consumer use. In the EU ETS area, the carbon emissions of this metal have been accounted and paid for, albeit with a potentially higher share of free allocation of EUAs at the time of production.

The loophole risks incentivising resource shuffling.

A key oversight in the CBAM is the failure to recognise that approximately 30% of all primary aluminium produced becomes process scrap before being remelted and turned into a final product. This amounts to more than 20 million tons of aluminium globally. All process scrap is re-melted and re-used. Meanwhile, EU demand for primary aluminium is only about 7 million tonnes. Assigning zero emissions to remelted process scrap in imported aluminium products, therefore, opens the possibility to cover most of the EU’s need for aluminium by re-shuffling products based on re-melted process scrap. This has no positive climate impact, as recycling rates for pre-consumer scrap are already > 99 %, and the emissions of the production process are already in the atmosphere.

This regulatory error not only creates a legally exploitable loophole in the CBAM system but also encourages non-European companies to both artificially increase the generation of industrial scrap in their production process, and to falsely label aluminium exported to Europe as containing “carbon-free” remelted aluminium.

Decision-makers can close this loophole. Here’s how:

As the discussion and voting on this issue within the European Commission Expert Group on the CBAM approaches, the urgency for the European Commission, Expert Group members and Member States to address this loophole cannot be overstated. For the CBAM to be effective, imported semi-fabricated products (billets, slabs, foundry ingots) must face the same carbon costs as the equivalent EU-manufactured products. This means:

- Equal Emissions for Remelted Scrap: Both the carbon emissions and the carbon cost must follow the metal. They cannot be artificially allocated to some products while others escape the cost. The CBAM should apply the same carbon costs to remelted process scrap in aluminium products as to primary aluminium, mirroring the carbon costs in the European aluminium value chain and reflecting the true environmental impact of the production processes outside Europe.

- Include aluminium scrap in the CBAM: Aluminium scrap, pre-consumer scrap as a first step, must be explicitly included in the CBAM scope both as product and as a precursor and assigned the same level of emissions as primary in the calculation methodology. Necessary updates to trade codes for aluminium scrap are essential to enable precise and equitable carbon accounting.

- Verification and Certification: Implementing third-party verified certificates to accurately track the metal’s emissions (including from scrap content) throughout its lifecycle is crucial. This will facilitate proper decarbonisation incentives and ensure uniform standards across all producers. European aluminium companies are already implementing such practices, which can feasibly be extended to importers of non-European products.

Adjusting the CBAM to close the scrap loophole is a small and perfectly implementable part of the larger CBAM framework. However, it is more than a regulatory tweak; it is a vital step to uphold the integrity of European aluminium industry, effectively contribute to the global fight against climate change, and incentivise the circular economy. Only by ensuring that all imported aluminium bears a fair and equivalent carbon cost compared to European production will the CBAM be able to fulfil its intended role.

About the authors:

Hydro

Norsk Hydro is Europe’s largest aluminium company, with operations in 20 European countries and employing over 18,000 people across the continent. The company’s global operations in more than 40 countries span the entire aluminium value chain, from bauxite mining, aluminium refining, and aluminium smelting and recycling to the world’s largest network of aluminium extruders. Hydro is also producing renewable energy to power the green industrial transition and expanding into battery materials production. The company’s roadmap to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 or sooner is aligned with the objectives of the EU Green Deal.

www.hydro.com

Contact: Ana Mingo, Senior Manager, EU Affairs – Energy & Climate, Hydro

ana.mingo@hydro.com

Alcoa

Alcoa Corporation is active in all aspects of the upstream aluminum industry with bauxite mining, alumina refining, and aluminum smelting and casting. The Company has direct and indirect ownership of 27 locations across nine countries on six continents, including Iceland, Norway and Spain. Alcoa has an ambition to reach net-zero emissions (Scope 1 and Scope 2) by 2050, with interim targets to achieve a 30% reduction by 2025 and a 50% reduction by 2030.

www.alcoa.com

Contact: Lambert Guilbault, Senior Manager, Corporate Affairs, Europe, Alcoa

lambert.guilbault@alcoa.com

Sandbag

Sandbag in a non-profit climate change think tank based in Brussels that uses data analysis and targeted advocacy campaigns to improve EU climate policies. Their research focuses on EU programmes and policies such as the EU Emissions Trading Scheme, the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and the decarbonisation of heavy industry.

www.sandbag.be

Contact: Aymeric Amand, Policy Officer, Carbon Pricing & Industrial Decarbonisation, Sandbag

aymeric.amand@sandbag.be

Bellona Europa

Bellona Europa is an independent, non-profit organisation that meets environmental and climate challenges head on. We are solutions-oriented and have a comprehensive and cross-sectoral approach to assess the economics, climate impacts and technical feasibility of necessary climate actions. To do this, we work with civil society, academia, governments, institutions, and industries.

www.bellona.org

Contact: Francesco Lombardi Stocchetti, Policy Advisor, Sustainable Economy, Bellona Europa

francesco@bellona.org

[1] Sandbag (2024) A Scrap Game: Impacts of the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. In this simulation, the price increase caused by the phase-out of free allocation assumes an EU carbon price of €60 per tCO2e. The analysis only considers the reduction of free allocation after 2025 and not carbon costs already borne in 2025.

Photo by Heiko Küverling on Canva

Read More:

The EU CBAM gives a boost to Algeria’s iron exports

Sandbag’s brief assesses how the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) may affect Algeria’s iron and steel exports. It finds that although Algeria’s overall exposure to CBAM is limited, rising EU carbon costs are likely to increase EU market prices, with implications for the revenues and competitiveness of Algerian exports.

CBAM and Fertiliser Inflation in 2026: The facts behind the numbers

Estimates suggesting that the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) could increase fertiliser prices by up to 30% have brought a central question into focus: how

significant is the inflationary impact likely to be?

The CBAM dividend for Namibia and Ghana

This research note shows that Namibia and Ghana are likely to benefit from the CBAM, as EU price increases linked to the EU ETS outweigh CBAM fees under current exports. It also sets out transparent transformation scenarios, based on announced industrial projects, to show how expanded and lower-emissions production could further increase export revenues over time.