On July 6th 2017 Business Europe released a study with consulting firm FTI Compass Lexecon examining reform options for the the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). As negotiations on this file are advancing during the second round of trialogues, scheduled to take place later today, July 10th, Sandbag has highlighted the following critical shortcomings in the study’s assumptions.

- No account for policy overlap

While difficult to measure, assuming no overlap means that the Business Europe study (see Page 10) indicates a higher increase in the carbon price during Phase IV than is likely.

The 2020 modelling from the Commission’s Impact Assessment has been overtaken by developments in real emissions as a result of policy interactions and exogenous factors that were not taken into account at the time (see Putting the ETS in context, Sandbag, 2015). Given that Phase IV of the EU ETS is scheduled to run for a whole decade, longer than any previous Phase and covering more than one economic cycle, we can already be certain there will be some overlap. The precise extent of the overlap is somewhat uncertain, which is why in our own studies, we operate with both a base case and a low emissions scenario.

2. No guarantee of meeting future emissions targets

The Business Europe study says: “In all scenarios, irrespective of changes regarding increased flexibility of free allowances or changes to the MSR, emission reductions will stay in line with the EU decarbonisation targets trajectory.”

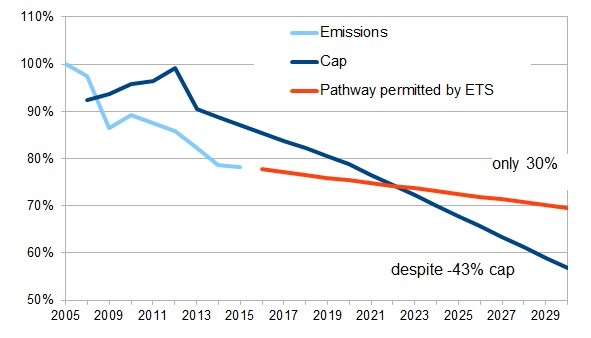

This is disingenuous. For as long as there is surplus in circulation in the market, emissions can INCREASE and still appear to be in line with the targeted trajectory for 2030 (and presently, we are not on track to meeting the 2050 goals by any measure). As it stands, there is nothing in either reform proposal that would prevent the market surplus from being used up to increase emissions and still the EU being ‘compliant’ with the target. In that case you can’t talk about emission reductions being consistent with the principle of a decreasing trajectory. By not addressing the surplus issue, we actually risk this whole reform leading to an accounting gimmick, which is what the statement in the study hints at.

The ETS surplus allows emissions to rise above the EU’s 2030 target

3. No guarantee of a significant carbon price throughout Phase IV

The final conclusion of the study seems to disagree with the first conclusion, as follows.

- On one hand we are told that “The cancellation of allowances envisioned by the Council and Parliament would limit the growth of the MSR in the long term, but it would have only a limited impact (if any) on prices and emissions over Phase IV”;

- On the other, the first thing the study promises is that “The (temporary) doubling of MSR intake rate would facilitate the market re-balancing as early as 2017 with agents taking speculative positions in anticipation of higher carbon prices in the future.”

The latter assumption is based on a long-term market hedging behaviour; however, we know that the EUA market is a very short-term one.

Re-balancing the market in 2017 implies achieving a balance between the supply and demand before the MSR even starts operating in 2019 (with a double intake rate for the first four years). For that to happen, you would need a significant shift in market behaviour – but the market barely reacted to the Council General Approach and to the Parliament position, with prices currently at 5,53€.

4. The carbon price isn’t rising, and the overall surplus isn’t falling

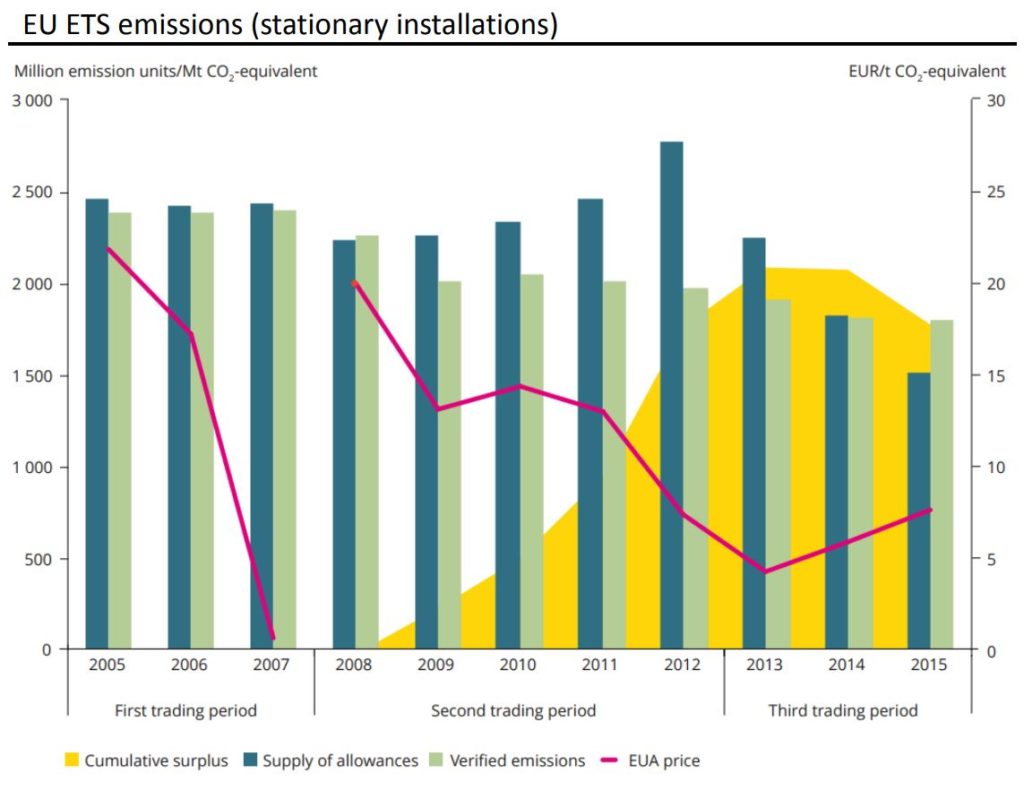

Business Europe’s graph (see below) has data up to 2015, showing cumulative surplus decreasing, and the carbon price increasing. The fall in the surplus on the market was temporary, due to backloading, and the overall surplus will continue to climb when these allowances return (albeit off the market and into the MSR).

Furthermore, in 2015 there was wide hope of strong reform and hence a slight price rise which has subsequently disappeared. For a year now the price has hovered around €5.

Graph from Business Europe’s ETS reform study, which only has data to 2015, and so wrongly implies the carbon price is rising and the cumulative surplus is falling

Policymakers discussing ETS reform this evening should be sceptical of Business Europe’s conclusions. The EU ETS is far from mended, and even under the most ambitious trialogue outcome, the carbon price is unlikely to reach the level needed for delivering cost-effective emission reductions.