Contact pieter@sandbag.org.uk for more information

-

Provisional ESR deal puts the EU off-track to achieve its 2030 target

-

Some improvements were agreed, but insufficient to close the ambition gap – Review in 2024 becomes essential

-

EU states have wildly different challenges – Cooperation through Project Based Mechanisms will be necessary to truly share effort cost-effectively

21st December, Brussels – Today, the Council and the European Parliament have reached a provisional agreement to reform the Effort Sharing Regulation, the sister climate policy to the Emissions Trading System, covering agriculture, buildings and transport emissions. Despite some steps in the right direction, the end deal puts these sectors off track to reach the 2030 target.

At the core of negotiations was the starting point for the emission trajectory towards the 2030 target of (-30% compared to 2005). Efforts from the European Parliament to start the journey based on progress already made was met by fierce resistance from national governments. Despite the courageous perseverance of several shadow rapporteurs in defense of ambition, in the end the stand-off resulted in only a minor improvement compared to the Council position. By delaying the much-needed transition in the non-ETS sectors, the EU’s 2030 target is reduced to -28.5%. With the introduction of external flexibilities – with the EU ETS and the LULUCF – the actual reduction required from the Effort Sharing sectors is diluted further to -26%.

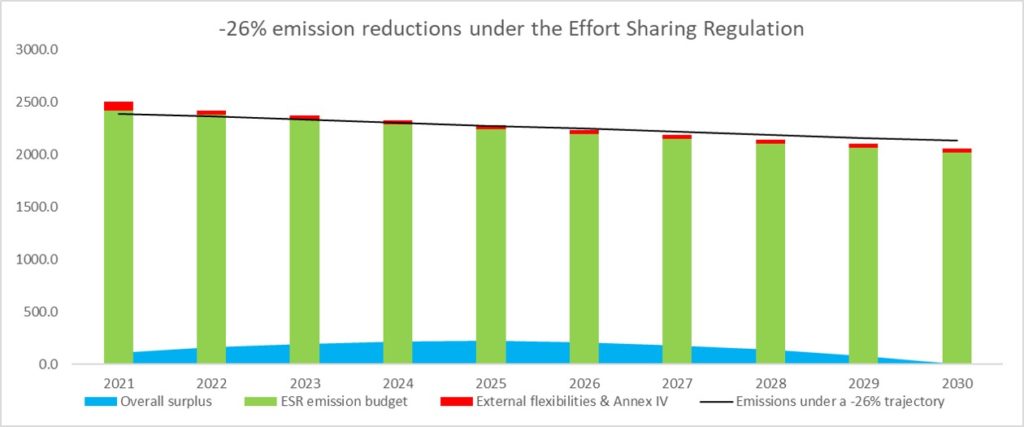

The chart above illustrates what would happen under the ESR if emissions would follow a trajectory towards a -26% reduction in 2030. Due to a high starting point in the beginning of 2021-2030 and the availability of external flexibilities, a surplus is built up until 2025 which can then be carried over to cover deficits in the years 2026-2030.

Fortunately, efforts by the European Parliament and a group of more ambitious member states have prevented further disaster. If the ESR would have repeated the same mistakes as the EU ETS – starting the trajectory based on outdated targets – it would have become completely irrelevant. Luckily the Commission recognized this risk and made a first step in the right direction for the co-legislators to build on. And although Council and Parliament have failed to make real use of this opportunity, they have at least not reverted this improvement – as initially demanded by a number of member states. Furthermore, the European Parliament has ensured that the use of ETS allowances under the Effort Sharing Regulation does not undermine the recently agreed strengthening of the ETS Market Stability Reserve. Finally, a limit of 30% on banking of excess allowances – although too high to make a real difference – sets a precedent and is a first step to reflect the progression principle under the Paris Agreement.

Nevertheless, the deal is too weak to guarantee delivery on the -30% target, let alone to prepare the non-ETS sectors for a net-zero emission objective in line with the Paris Agreement. The EU must therefore do its homework so that it is ready to step up ambition at the first review in 2024. A first step in this exercise is the development of strong National Action Plans with credible measures to set our transport, building, agricultural and waste systems on a credible track towards our long term targets.

Project Based Mechanisms

Whereas the required effort from the EU as a whole is limited at best, the picture varies when looking at different member states. Due to highly differentiated targets that neglect reduction potential, some member states face real challenges whereas others risk missing out on cost-effective mitigation opportunities and the many co-benefits they provide. This is problematic as it prevents a cost-effective achievement of the climate targets and so undermines political will for further action. Luckily, the ESR does provide a solution by promoting cooperation between member states such as mitigation projects and trading of emission allocations (the revenues of which should be reused for further action). It is now up to the member states to make use of these possibilities to bridge the gap between national targets and potential, and to reap the benefits of a cost-effective transition towards a net-zero emission world. For more info on the potential of Project Based Mechanisms, see our previous work here.

The agreement will now go for formal approval by the Council and Parliament in January.

Pieter-Willem Lemmens, Head of Analysis at Sandbag commented:

The EU has more to do to match the ambition of the Paris Agreement: efforts will inevitably have to be upped in the 2024 review. The gap between targets and reduction potential is giving member states cold feet – and there’s a risk they fail to build on the emissions reductions already made. They must now use the possibility of true intra-European cooperation such as cross-border mitigation projects and trading in order to rebalance the ESR and unlock cost-effective emissions reductions.