Last week’s final trilogue on the Phase IV EU ETS revision has left us all stranded in an unmoored boat on rocky waters, still far from the safe shore of Paris compatible EU climate policy.

Sandbag has been involved in this reform, producing analysis and advocacy, since it began in 2015. Many of our recommendations have survived the negotiations, such as voluntary unilateral cancellation of allowances by Member States, the idea of double surrender as translated into an increased MSR intake rate, and overall cancellation of 3 bil tonnes of CO2 from the surplus. However, the main elements are still missing which would have made this reform worthy of a post-Paris climate leadership position that the EU claims.

We regret specific derogations that will put industry sectors and certain member states off the track towards our long-term targets (e.g. steel and iron, coal use for district heating for the poorest EU member states). The reality is that the EU needs all countries and all incumbents to work together towards decarbonisation, otherwise some will be left behind in the process. Not leaving any more room for emissions to increases in low GDP countries would have been the optimal way to ensure the Modernisation Fund can play its role of being an almost ‘Marshall plan’ for the region.

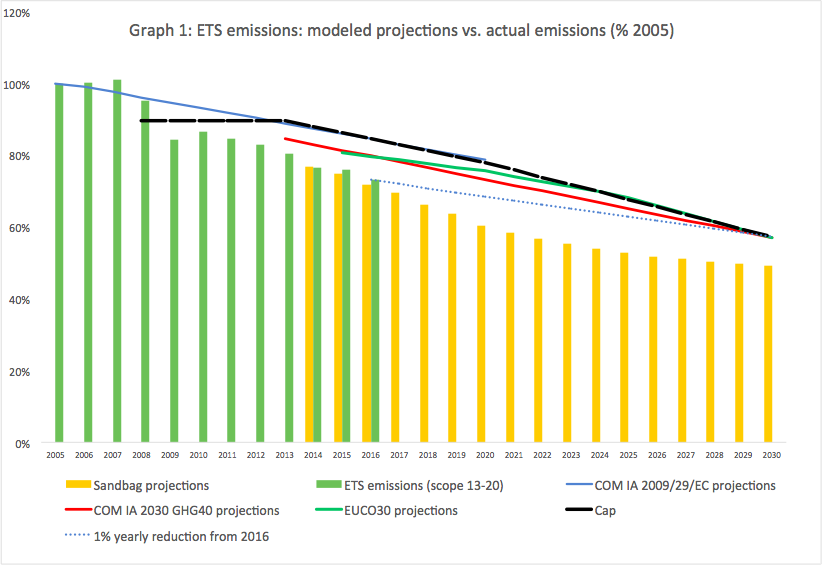

Experience has shown us that previous modelling by the Commission has not properly factored in market uptake rates of new technologies or of innovation. Ever since the start of the EU ETS, the cap has been set based on modeled policy scenarios that have underestimated the reduction potential in the ETS sectors (see graph 1 below).We would have liked the lesson to be learned and for the Phase IV reform to result in a EU policy that both stimulates innovation and factors it into emissions targets. Instead, the current reform is protecting incumbents and assuming tomorrow’s problem can be solved with yesterday’s technologies. This is clearly an outdated assumption.

In 2016 alone the ETS sectors were at -26,5% reduction compared to 2005. This implies these sectors will only need to reduce on average 1% per year to do their part of the -40% target (-43% compared to 2005), see graph 1.

Since the ETS started in 2005 emissions have been falling faster than expected and EU policy instruments have been failing to catch up with that reality ever since. We shouldn’t be afraid to raise the bar and make sure that the ETS can keep pace. In particular, a core element of flexibility in design continues to be missing. Instead of giving certainty to investors, this further increases the uncertainty regarding the relevance, or better said, the possibly continued inadequacy of the EUA price throughout Phase IV.

The biggest risk going forward is that the reductions achieved in the past could be used to increase emissions in the future. This is out of line with the Paris Agreement principle of successive tightening and the whole notion of ‘peaked’ emissions which would apply to the EU (art 2, 4 and 14 of Paris Agreement). More specifically, thanks to the progress made so far, we could be in a situation where, in aggregate, the ETS sectors could follow a trajectory towards a reduction of only -35% by 2030 (or even -32% when assuming no net demand from aviation) and still have just enough EUAs to cover their obligations[1]. This means that if we want to guarantee the ETS target of – 43% is ensured (which should be considered as an absolute minimum, given the overall ‘at least -40%’ target) , the cap has to be tightened to reflect progress made. This step would also bring the ETS in line with the legal principles in the Paris Agreement, despite it probably being still far from aligning it with the agreed temperature increase scenarios foreseen therein.

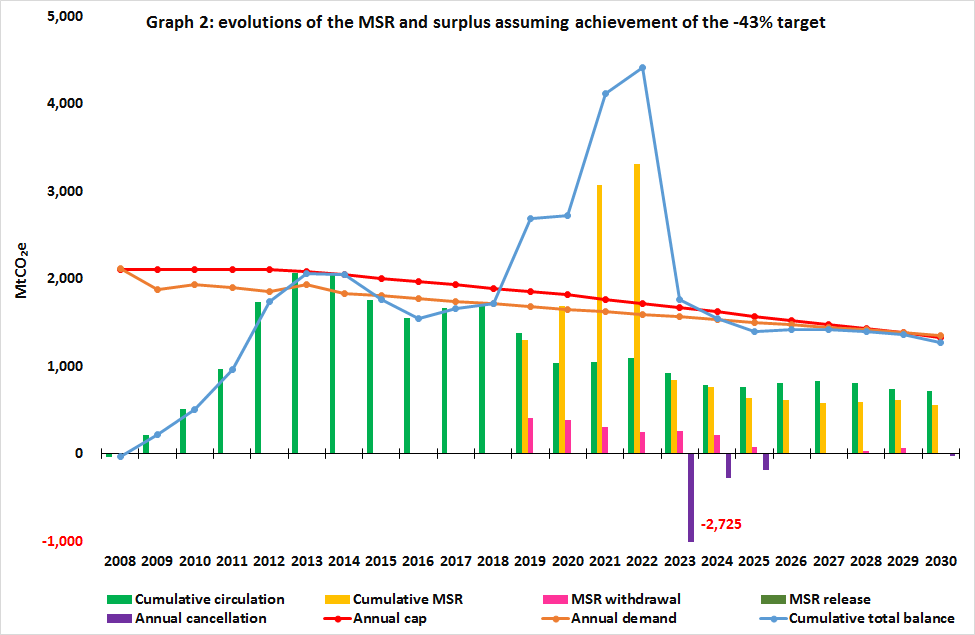

As it stands, this reform is not enough to ensure the environmental integrity of the 2030 targets. Even with the strengthened MSR, achieving the -43% reduction target by 2030 would lead to a persistent surplus of 721 million by 2030 (with another 556 million in the reserve)[2]– see graph. 2. Clearly the structural measures to address the surplus – although a step in the right direction – are insufficient to tackle the problem in a scenario where the EU actually delivers on its international targets. Sandbag regrets that policy makers have not fully used this opportunity to make the ETS less obsolete and more relevant to the global and European level plans to reach a net zero economy later this century.

In addition to an overall lack of ambition, policy makers have also failed to reform the allocation rules to drive innovation in the industrial sectors while maintaining effective protection against the risk of carbon leakage. Despite the very thorough Impact Assessment the European Commission has carried out on the 2030 package, which ranked a tiered approach to carbon leakage as the ideal method to allocate free allocation, this reform has managed to lose the opportunity to protect our industries in a more targeted manner. This seems ignore the fact that free allocation to industry is in fact a temporary derogation from the Polluter-Pays-Principle enshrined in the EU Treaties (Art. 191(2) TFEU). In an unexpected turn of the situation, the European Commission was the least ambitious of the institutions during the negotiations – less ambitious than Parliament and Council.

Regretfully, the revision was concluded as the COP23 unfolds in Bonn. The COP where the US federal government is flaunting its last flirtation with the dying coal industry. This was a (missed) chance for the EU to step in and provide leadership on carbon markets.. Instead, the EU has taken a tiny step in the right direction, but nevertheless this is a huge missed opportunity to do what was actually needed.

At Sandbag we are strong believers that climate policy can be designed smartly and in terms of the ETS, we have proposed several ways in which this could have been achieved. While it would be sad to see the ETS disappear due to irrelevance, we are hopeful that a scheme which can work in tandem with complementary national policies can eventually be put in place. In Sandbag, we are already looking forward to the 2018 Facilitative Dialogue as the next opportunity for the Commission to reassess the ETS and its adequacy in meeting internationally agreed temperature goals. 2018 will also be an opportunity for the Commission to look hard into its original modelling, in the context of designing the Mid-Century Strategy, in order to assess whether the models used so far have indeed been fit for purpose.

Notes

[1] Assuming a linear trajectory between the latest verified emissions in 2016 and a -32% reduction by 2030, and taking into account the trilogue outcome: a 24% MSR intake rate until 2023, dropping to 12% as of 2024. The Innovation Fund is assumed to be monetized in 2021 and 2022 (200 million EUA’s in each year).

[2] Assuming a linear trajectory between the latest verified emissions in 2016 and a -43% reduction by 2030, and taking into account the trilogue outcome: a 24% MSR intake rate until 2023, dropping to 12% as of 2024. The Innovation Fund is assumed to be monetized in 2021 and 2022 (200 million EUA’s in each year).